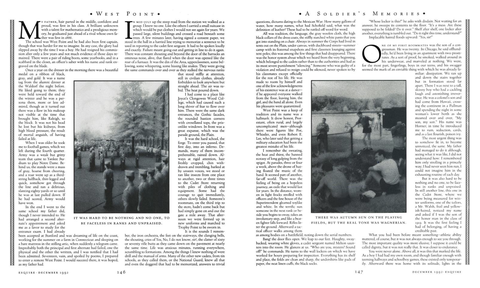

James Salter’s Famous Essay About His Time as a West Point Cadet

This article originally appeared in the December 1992 issue of Esquire. You can find every Esquire story ever published at Esquire Classic.

My father, hair parted in the middle, confident and proud, was first in his class. A brilliant unknown with a talent for mathematics and a prodigious memory, he graduated just ahead of a rival whose own father was first in 1886.

The school was West Point and he had also been first captain, though that was harder for me to imagine. In any case, the glory had slipped away by the time I was a boy. He had resigned his commission after only a few years and not much evidence of those days remained. There were a pair of riding boots, some yearbooks, and in a scabbard in the closet, an officer’s saber with his name and rank engraved on the blade.

Once a year on the dresser in the morning there was a beautiful medal on a ribbon of black, gray, and gold. It was a name tag from the alumni dinner at the Waldorf the night before. He liked going to them; they were held toward the end of the winter and he was a persona there, more or less admired, though as it turned out there was a flaw in his makeup not visible at the time that brought him, like Raleigh, to the block. It was not his head he lost but his kidneys, from high blood pressure, the result of mortal anguish, of having failed at life.

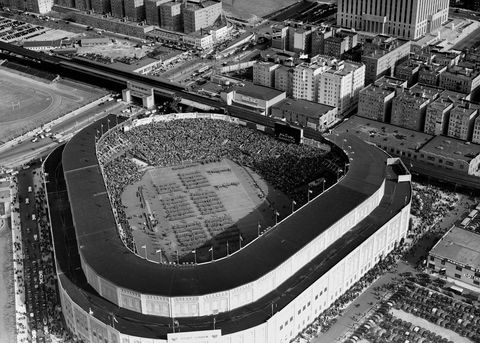

When I was older he took me to football games, which we left during the fourth quarter. Army was a weak but gritty team that came to Yankee Stadium to play Notre Dame. Behind us, the stands were a mass of gray, hoarse from cheering, and a roar went up as a third-string halfback, thin-legged and quick, somehow got through the line and ran a delirious, slanting eighty yards or so until he was at last pulled down. If he had scored, Army would have won.

In the end I went to the same school my father did, though I never intended to. He had arranged a second alternate’s appointment and asked me as a favor to study for the entrance exam. I had already been accepted at Stanford and was dreaming of life on the coast, working for the summer on a farm in Connecticut and sleeping on a bare mattress in the stifling attic, when suddenly a telegram came. Improbably both the principal and first alternate had failed, one the physical and the other the written, and I was notified that I had been admitted. Seventeen, vain, and spoiled by poems, I prepared to enter a remote West Point. I would succeed there, it was hoped, as my father had.

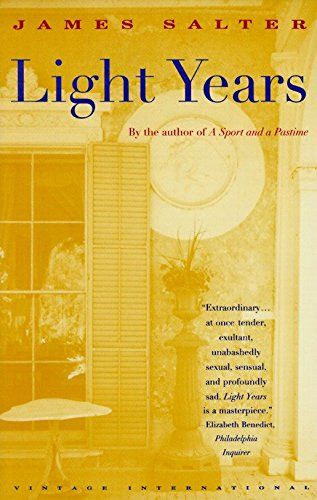

In mid-July up the steep road from the station we walked as a group. I knew no one. Like the others I carried a small suitcase in which would be put clothes I would not see again for years. We passed large, silent buildings and crossed a road beneath some trees. A few minutes later, having signed a consent paper, we stood in the hall in a harried line trying to memorize a sentence to be used in reporting to the cadet first sergeant. It had to be spoken loudly and exactly. Failure meant going out and getting in line to do it again. There was constant shouting and beyond the door of the barracks an ominous noise, alive, that flared when the door was opened like the roar of a furnace. It was the din of the Area, upperclassmen, some bellowing, some whispering, some hissing like snakes. They were giving the same commands over and over as they stalked the nervous ranks that stood stiffly at attention, still in civilian clothes, already forbidden to look anywhere but straight ahead. The air was rabid. The heat poured down.

I had come to a place like Joyce’s Clongowes Wood College, which had caused such a long shiver of fear to flow over him. There were the same dark entrances, the Gothic facades, the rounded bastion corners with crenellated tops, the prisonlike windows. In front was a great expanse, which was the parade ground, the Plain.

It was the hard school, the forge. To enter you passed, that first day, into an inferno. Demands, many of them incomprehensible, rained down. Always at rigid attention, hair freshly cropped, chin withdrawn and trembling, barked at by unseen voices, we stood or ran like insects from one place to another, two or three times to the Cadet Store returning with piles of clothing and equipment. Some had the courage to quit immediately, others slowly failed. Someone’s roommate, on the third trip to the store, hadn’t come back but had simply gone on and out the gate a mile away. That afternoon we were formed up in new uniforms and marched to Trophy Point to be sworn in.

It is the sounds I remember, the iron orchestra, the feet on the stairways, the clanging bells, the shouting, cries of Yes, No, I do not know, sir!, the clatter of sixty or seventy rifle butts as they came down on the pavement at nearly the same time. Life was anxious minutes, running everywhere, scrambling to formations. Among the things I knew nothing of were drill and the manual of arms. Many of the other new cadets, from tin schools, as they called them, or the National Guard, knew all that and even the doggerel that had to be memorized, answers to trivial questions, dictums dating to the Mexican War. How many gallons of water, how many names, what had Schofield said, what was the definition of leather? These had to be rattled off word for word.

All was tradition, the language, the gray woolen cloth, the high black collars of the dress coats, the stiffly starched white pants that you got into standing on a chair. Always in summer the Corps had lived in tents out on the Plain, under canvas, with duckboard streets—summer camp with its fraternal snapshots and first classmen lounging against tent poles; this was among the few things that had disappeared. There was the honor system about which we heard from the very beginning, which belonged to the cadets rather than to the authorities and had as its most severe punishment “silencing.” Someone who was guilty of a violation and refused to resign could be silenced, never spoken to by his classmates except officially for the rest of his life. He was made to room by himself and one of the few acknowledgments of his existence was at a dance—if he appeared everyone walked from the floor, leaving him, the girl, and the band all alone. Even his pleasures were quarantined.

West Point was a keep of tradition and its name was a hallmark. It drew honest, Protestant, often rural, and largely uncomplicated men—although there were figures like Poe, Whistler, and even Robert E. Lee, who later said that getting a military education had been the greatest mistake of his life.

I remember the sweating, the heat and thirst, the banned ecstasy of long gulping from the spigot. At parades, three or four a week, above the drone of hazing floated the music of the band. It seemed part of another, far-off world. There was the feeling of being on a hopeless journey, an exile that would last for years. In the distance, women in light frocks strolled with officers and the fine house of the Superintendent gleamed toylike and white. In the terrific sun someone in the next rank or beside you begins to sway, takes an involuntary step, and like a beaten fighter falls forward. Rifles litter the ground. Afterward a tactical officer walks among them as among bodies on a battlefield, noting down the serial numbers.

Bang! the door flies open. We leap to our feet. Haughty, swaybacked, wearing white gloves, a cadet sergeant named Melton saunters into the room. He glances at us. “Who are you, misters? Sound off!” he commands. He turns to the wall lockers on which we have worked for hours preparing for inspection. Everything has its shelf and place, the folds are clean and sharp, the undershirts like pads of paper, the neat linen cuffs, the black socks.

“Whose locker is this?” he asks with disdain. Not waiting for an answer, he sweeps its contents to the floor. “It’s a mess. Are these supposed to be folded? Do it over.” Shelf after shelf, one locker after another, everything is tumbled out. “Do it right this time, understand?”

Implacable hatred floods upward: “Yes, sir!”

One of my first roommates was the son of a congressman. He was twenty. In Chicago, he said offhandedly, he’d been living in an apartment with two prostitutes. As a sort of proof, he smoked, walked around in his underwear, and marveled at nothing. We were, for the most part, fingerlings, boys in our teens, and his swagger seemed the mark of an enviable thing with which he was already familiar: dissipation. We ran up and down the stairs together but in formation stood far apart. There I was next to a tall, skinny boy who had a cackling laugh and astonishing irreverence. He was a colonel’s son and had come from Hawaii, crossing the continent in a Pullman and spending the night in some woman’s lower berth as she moaned over and over, “My son, my son.” His name was Horner; in time he introduced me to rum, seduction, cards, and as a last flourish, poison ivy.

The most urgent thing was to somehow fit in, to become unnoticed, the same. My father had managed to do it although, seeing what it was like, I did not understand how. I remembered him only strolling in a princely way; I had never seen him run, I could not imagine him in the exhausting routine of each day.

But it was also hard to be nothing and no one, to be faceless in ranks and unpraised. In still another line, this one in the Cadet Store, where we were being measured for winter uniforms, one of the tailors, a Mr. Walsh, frail and yellowish-haired, noticed my name and asked if I was the son of the honor man in the class of 1919. It was the first feeling I had of belonging, of having a creditable past.

What you had been before meant something—athletic ability mattered, of course, but it was not always enough to see you through. The most important quality was more elusive; I suppose it could be called dignity, but it was not really that. It was closer to endurance.

You were never alone. Above all, it was this that marked the life. As a boy I had had my own room, and though familiar enough with teeming hallways and schoolboy games, these existed only temporarily. Afterward there was home with its solitude, lights in the evening, the rich smell of dinner. There was nothing of that at West Point. We brushed shoulders everywhere, as if it were a troopship, and waited a turn to wash and shave. In the earliest morning, in the great summer kiln of the Hudson Valley, we stood for long periods at strict attention, dangerous upperclassmen drifting behind us sullenly, the whole of the day ahead. Over and over to make the minutes pass I recited lines to myself, sometimes to the bullet-hard beat of drums, buried and lost, but for the moment wrapped in words.

I was an unpromising cadet, not the worst but a laggard. Among the youngest, and more immature than my years, I had neither the wisdom of country boys who knew beasts and the axioms of hardware stores, nor the toughness of the city. I had been forced to learn a new vocabulary and new meanings, what was meant by polished, for instance, or neatly folded. For parade and inspections we wore eighteenth-century accessories, crossed white belts and dummy cartridge box, with breastplate and belt buckle shined to a mirrorlike finish. In the doorway of the room at night, before taps, we sat feverishly polishing them. Pencil erasers and jeweler’s rouge were used to painstakingly rub away small imperfections, and the rest was done with a constantly refolded polishing cloth. It took hours. The terrible ring of metal on the floor—a breastplate that had slipped from someone’s hand—was like the dropping of an heirloom.

At the end of the summer, assignment to regular companies was made. There were sixteen companies, each made up of men who were approximately the same height. Drawn up in a long front before parade, the tallest companies were at each end grading down to the shortest in the middle. The laws of perspective made the entire Corps seem of uniform size, and as it passed in review, bayonets at the same angle, legs flashing as one, it looked as if every particle of the whole must be well-formed and bright. The tall companies were known to be easygoing and unmilitary in barracks, but among the runts it was the opposite. To even pass by their barracks was hazardous. This was not only fable but fact.

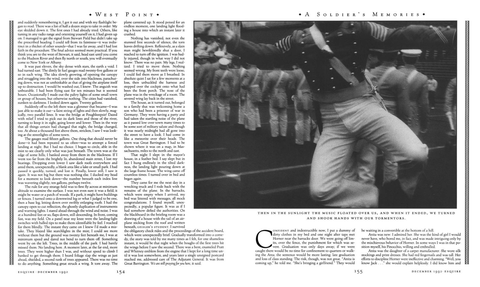

The stone barracks were arranged around large quadrangles called areas. Central Area was the oldest, and on opposite sides of it were South Area and North Area and a small appendix near the gym called New North. They were distinct, like provinces, though you walked through several of them every day. Beyond and unseen were the leafy arrondissements where West Point seemed like a serene river town. In mild September, with classes about to begin, it settled into routine. There was autumn sun on the playing fields but the real tone was Wagnerian. We passed by the large houses, all in a long row, of the colonels, heads of academic departments, some of them classmates or friends of my father, old brick houses to which I would one day be invited for Sunday lunch.

We had clean slates. All demerits from the summer had been removed and we were as men paroled. Demerits were a black mark and a kind of indebtedness. The allowance was fifteen a month. Beyond that, there were punishment tours, one hour for each demerit, an inflexible rate of exchange. The hours were spent on the Area walking back and forth, rifle on shoulder, and with this came a further lesson: At the inspection, which took place before the tours began, demerits were frequently given out. For shoes with a scuff mark accidentally made or brass with the least breath of tarnish you could receive more tours than you were able to walk off.

We had learned the skills of a butler, which were meant to be those of gentry. We wore pajamas and bathrobes, garters for our socks. Fingernails were scrubbed pink and hair cut weekly. We learned to take off a hat without touching the bill, to sleep on trousers carefully folded beneath the mattress to press them, to announce menus, birthdays, and weekend films with their cast. Like butlers we had Sunday off, but only after mandatory chapel.

Three times a day through three separate doors the entire Corps, like a great religious order, entered the mess hall and stood in whispery silence—there was always muted talk and menace—until the command, “Take seats!” With the scrape of chairs the roar of dining began. Meals were a constant terror and as if to enhance it, near their end the orders of the day were announced, often including grave punishments awarded by the regimental or brigade boards. At the ten-man tables upperclassmen sat at one end, plebes at the other. We ate at attention, eyes fixed on plates, sometimes made part of the conversation like an amusing servant but mostly silent or bawling information. At any moment, after being banged on the table, a cup or glass might come flying. The plebe in charge of pouring looked up quickly, hands ready, crying, “Cup, please!” It was a forbidden practice but a favorite. A missed catch was serious since the result might be broken china and possible demerits for an upperclassman. It was better to be hit with a cup in the chest or even the head.

“Sit up!” was a frequent command. It meant “stop eating,” the consequence of having failed to know something—passing the wrong dish or putting cream in someone’s coffee who never took it that way—and might result in no meal at all, though usually at the end permission was given to wolf a few bites. Somewhere, in what was called the Corps Squad area, the athletes, plebes among them, were eating at ease.

Like a hereditary lord’s, the table commandant’s whim was absolute. Some were kindly figures fond of teasing and schoolboy skits. Others were more serpentlike, and most companies had a table that was Siberia ruled by a stern disciplinarian, in our case an ugly Greek first classman, dark and humorless. In the table assignments you made your way downward to it, and there, among the incorrigibles, even felt a kind of pride.

The hour before dawn, everything silent, the air chill with the first bite of fall. The Area was empty, the hallway still. The room was on the second floor at the head of the stairs, the white name cards pale on the door. I waited for a moment, listening, and cautiously turned the knob. Within it was dark, the windows barely distinguishable. At right angles, separated by desks, were the beds. Waters, a blue-jawed captain, the battalion commander, slept in one. Mills, a sergeant and squad leader, was in the other. I could not hear them breathing; I could hear nothing, the silence was complete. I was afraid to make a sound.

“Sir!” I cried, and shouting my name went on, “reporting as ordered, ten minutes before reveille!” A muffled voice said, “Don’t make so much noise.” It was Mills. His quilt moved higher against the cold and as an afterthought he muttered, “Move your chin in.”

I stood in the blackness. Nothing, not the tick of a clock or the creaking of a radiator. The minutes had come to a stop. I might stand there forever, invisible and ignored, while they dreamed.

It was Mills who had ordered me to come, for some misdemeanor or other, every morning for a week. He was my squad leader but more than that was famous, known to everyone as king of the goats.

The first man in the class was celebrated; the second was not, nor any of the rest. It was only when you got to the end that a name became imperishable again, the last man, the goat, and it was with well-founded pride that a goat regarded himself. Custer had been last in his class, Grant, nearly. The goat was the Achilles of the unstudious. He was champion of the rear. In front of him went all the main body with its outstanding and also mediocre figures; behind him was nothing, oblivion.

It was a triumph like any other, if you were not meant for the classroom, to end up at the very bottom. Those with worse grades had gone under, those with only slightly better were lost in the crowd. Mills had a bathrobe covered with stars. Each one represented the passing of a turn-out examination, the last, all-or-nothing chance in a failed subject—his robe blazed with them. He had come to this naturally; his father had made a good run at it and been fifth from last in 1915. Mills knew the responsibilities of heritage. He had fended off the attacks of men of lesser distinction who nevertheless wanted to vault to renown. Blond and good-looking, he was easy to admire and far from ungifted. A well-executed retreat was said to be among the most difficult of all military operations, at which some commanders were adept. It meant passing close to the abyss, skirting disaster, and surviving by a hair. It was a special realm with its tension and desperate acts, with men who would purposely spill ink over their drawing in engineering on the final day when nothing else, no possibility, was left.

Mills was also a good athlete. He had come from South Carolina and gone to The Citadel for a year. There was a joy of life in him and a kind of tenderness untainted by the merely gentle.

Nothing more had been said to me. I stood in silence. There was neither present nor future. They were unaware of me but I was somehow important, proof of their power. I began to feel dizzy, as if the floor were tilting, as if I might fall. I had lost track of how long I had been there; time seemed to have stopped when from the distance came a single, clear report: the cannon.

Immediately, like a demonic machine, the sounds begin. Outside in the void, drums explode. Someone is shouting in the hallway, “Sir, there are five minutes until assembly for reveille! Uniform, dress gray with overcoats! Five minutes, sir!” Music is playing. Feet can be heard overhead and on the stairs. The hives of sleeping men are spilling out. The drums begin again.

In the room, not a movement. It is still as a vault. Four minutes until assembly. They have not stirred. The plebes are already standing in place with spaces between them that will be filled by unhurrying upperclassmen. The drums start once more. Three minutes.

Something is wrong. For some reason they are not going to the formation, but if I am late or, unthinkable, miss it entirely…. The clamor continues, bugles, drums, slamming doors. Two minutes now. Should I say something, dare I? At the last moment a bored voice murmurs, “Post, dumbjohn.”

I hurry down the steps and into the cold. Less than a minute remains. Hastily making square corners I reach my place in ranks just as two figures slip past, overcoats flapping, naked chests beneath: Waters and Mills. Fastening the last buttons Waters arrives in front of the battalion as the noise dies and final bells ring. He appears instantly resolute and calm, as if he had been waiting patiently all along. In a clear, deep voice he orders, “Report!”

I did not exist for Waters, and for Mills, barely. We marched early one Saturday, down to the river where the Corps boarded a many-decked white dayliner to sail to New York. At the football game that afternoon, jammed in the half-time crowd, Mills was coming the other way, by chance behind a very beautiful girl, just behind her with an expression of pure innocence on his face. As he passed me, he winked.

His class graduated early, that January of 1943, hastened by the war. There was a tremendous cheer as he walked up to receive his diploma, and for some reason I felt as they did, that he was mine. I thought of him for a long time afterward, the ease and godlike face of the last man in his class.

In the safety of that autumn, I foundered. The demerits began again—unpolished shoes, dirty rifle, late for athletics, Blue Book misplaced—there were fifty the first month. One night in the mess hall a spontaneous roar went up when it was announced that at the request of a British field marshal—I think it was Field Marshal Dill—all punishments were revoked. According to custom, a distinguished visitor could do that. The cheers passed over my head, so to speak, but the amnesty did not; I had thirty-five tours erased, seven weeks of walking.

Still I was swept along as if by a current. I felt lost. There were faces you did not recognize, formations being held no one knew where, the pressure of crammed schedules, the formality of the classrooms, the impersonality of everyone in authority from the distant Superintendent to the company tactical officers…. It was plain to see why they called it the Factory. It was a male world. In the gym we fought one another, wrestled one another, slammed into one another on darkened fields battling for regimental championships. There were no women except for nurses in the hospital and hardened secretaries, but there was the existence of women always, outside. An upperclassman had his laundry come back with a note pinned to the pajama bottoms, which had gone out with a stiffened area on them. A girl who worked in the laundry had written, The next time you feel like this, call me.

We were inmates. The world was fading. There were cadets who wet the bed and others who wept. There was one who hanged himself. In the gloom of the sally ports were lighted boards where grades from classes were posted at the end of the week. My roommate was failing in mathematics and I was in difficulty in languages. “Don’t worry,” the professor, a major, had said, “it’ll get tougher.” We stayed up after taps studying with a flashlight, exhausted and trying to comprehend italicized phrases in the red algebra book. “Let’s rest for a few minutes,” we said, and kneeling side by side on the wooden floor dozed briefly with only our upper bodies on the bed. Often we studied past midnight in the lavatory.

The field marshal’s gift was soon squandered. My name appeared on the gig sheet three or four times a week; I was walking tours and coming back to the room at dusk, dry from the cold and wary, putting my rifle in the rack, taking off my crossbelts and breastplate, and sitting down for a few minutes before washing for supper. Punishment had a moral, which was to avoid it, but I could not. There was something alien and rebellious in me. The ease with which others got along was mysterious. I was losing courage, the thing I always feared having too little of. I was losing hope.

In the first captain’s room in the oldest division of barracks there were the names of all those who had once had the honor. I wanted to see it, to linger for a moment and find my bearing as had happened long ago in the Cadet Store line. Late one Sunday afternoon, telling no one, I went there—nothing forbade it—and stood before the door. I nearly turned away but then, impulsively, knocked.

The first captain was in his undershirt. He was sitting at his desk writing letters and his roommate was folding laundry. He looked up, “Yes, mister, what is it?” he said.

Somehow I explained what I had come for. There was a fireplace and on the wall beside it was a long, varnished board with the names. I was told to have a look at it. The list was by year. “Which one is your father?” they asked. I searched for his name and for some reason missed it. My eye went down the column again. “Well?” It was inexplicable. I couldn’t find it; it wasn’t there. I didn’t know what to say. There had been some mistake, I managed to utter. I felt absolutely empty and ashamed.

My father, in a letter, was able to explain. His class, in wartime, had graduated early and had come back to West Point after the armistice as student officers. As highest-ranking lieutenant, the result of his academic standing, my father had been student commander. He called this being first captain and I realized later that I should never have brought it up.

He had been recalled and was now a colonel stationed in Washington. When he came up to visit we walked on the lawn near the Thayer Hotel in winter sunshine. Bits of the wide river glittered like light. I wanted him to counsel me and looking moodily at the ground recited from “Dover Beach.” What was I struggling for and what should I believe? It would be more clear later, he finally said. He had never forsaken West Point. He believed in it and would in fact one day be buried near the old chapel. He was counting on the school to steady me, fix me as the quivering needle in a compass firms on the pole, a process he did not describe but that in his case had been more or less successful.

There was the idea that you could be changed, that West Point could make you an aristocrat. In a way it did; it relied on the stoic, outdoor life that is the domain of the aristocrat: sport, hunting, hardship. Ultimately, however, it was a school of less-privileged classes with no true connection to the upper world. You were an aristocrat to sergeants and reserve officers, men who believed the myth.

It was a place of bleak emotions, a great orphanage, cold in its appearance, rigid in its demands. There was occasional kindness but little love. The teachers did not love their pupils or the coach the mud-flecked fullback—the word was never spoken although I often heard its opposite. In its place were comradeship and a standard that seemed as high as anyone could know. It included self-reliance and death if need be. West Point did not make character, it extolled it. It taught you to believe in difficulty, the hard way, and to sleep, as it were, on bare ground. Duty, honor, country. The great virtues were cut into stone above the archways and inscribed in the gold of class rings, not the classic virtues—not virtues at all, in fact, but commands. In life you might know defeat and see things you revered fall into darkness and disgrace, but never these.

Honor was second but in many ways it was the most important. Duty might be shirked, country one took for granted, but honor was indivisible. The word of an officer or cadet could not be doubted. One did not cheat, one never lied. At night a question was asked through the closed door, “All right, sir?” and the answer was the same, “All right.” It meant that whoever was supposed to be in the room was there and no one besides—one voice answered for all. Absences, attendance, all humdrum was on the same basis and anything written or signed was absolutely true. Even the most minor violation was grave. There was an honor committee; its proceedings were solemn; from its judgment there was no appeal. The committee had no actual disciplinary power. It was so august that anyone convicted—and there were no degrees of guilt, only thumbs up or down—was expected to resign. Almost always they did. Inadvertence could sometimes excuse an honor violation, but not much else. Word traveled swiftly—someone had been brought up on honor. A few days later there was an empty bed.

In the winter there were parades within the barracks area rather than on the Plain: the band, the slap of hands on rifles, the glint of steel, the first companies sailing past. One of the earliest, in the rain, was for the graduation of the January class. They were walking along the stoops afterward in the brilliance of their army uniforms, Roberts, Jarrell, Mills, all of them. The wooden packing boxes stenciled with their names and new rank were waiting to be shipped off, the sinks strewn with things they had no use for, that in the space of a single day had lost their value, cadet things they had not given away or sold, textbooks, papers. The next morning they, the boxes, everything was gone—it was like a divorced household, with them somehow went a sense of legitimacy and order. The new first class seemed unfledged—it would always exist in the shadow of the one gone on.

One afternoon near the end of winter we ordered class rings. The ring was a potent object, an insignia and reward. Heavy and gold, it was worn on the third finger of the left hand, the wedding finger, with the class crest inward until graduation. After, it was turned around so the academy crest would be closest to the heart. Engraved within was one’s name and “United States Army.” I had decided I wanted something more, perhaps not the non serviam of Lucifer, but a coda. Someone, I knew, somewhere, would take this ring from my lifeless finger and within find the words that would sanctify me. The line moved steadily forward, the salesman filling out order blanks and explaining the merits of various stones. Could I have something else engraved in my ring? I asked. What did I mean, something else? I wasn’t sure; I hadn’t decided, and I had the feeling I was taking up too much time. Finally he wrote “To follow” in the space for what was to be engraved.

Unknown to me, all this was overheard. That evening in the mess hall before “Take seats,” a cadet captain was ferreting his way between the tables, here and there whispering a question. I had never seen him before. He was looking for me. I saw him come around the table and the next moment he was beside me. Was I the one who didn’t want “United States Army” in his ring? he asked in a low voice. I didn’t have the chance to reply before he continued icily, “If you don’t think the U.S. Army is good enough for you, did you ever stop to think that you might not be good enough for the U.S. Army?” On the other side of me another face had appeared. They were converging from far off. “Did you ever make a statement that you would resign just before graduation?” someone said. It was true that I had. “Only facetiously, sir.” I could feel the sweat on my forehead. “Did you ever say you came here only for the education?” “No, sir!”

Their voices were scornful. They wanted to get a look at me, they said, they wanted to remember my face. “Mister, the Corps will see to it that you earn your ring.” It was useless to try to explain. Who informed them, I never knew. Later I realized it had been a classmate, of course. The worst part was that it all took place in front of my own company. I was confirmed as a rebel, a misfit.

Incidents form you, events that are unexpected, unseen trials. I defied this school. I took its punishment and its hatred. I dreamed of telling the story, of making that my triumph. There was a legendary book in the library said to have been written by a cadet, to contain damning description and to have been suppressed and all copies except one destroyed. It was called The Tin Soldier and was not in the card file nor did anyone I asked admit having heard of it. It was a kind of literary mirage though the title seemed real. If there were no such book, then I would write it. I thought of its power all that spring during endless hours of walking back and forth on the Area at shoulder arms. Pitiless and spare, it would be published in secret and read by all. Apart from that I was indifferent and tried to get by doing as little as possible since whatever I did would not be enough.

At the same time, kindled in me somehow was another urge, the urge to manhood. I did not recognize it as such because I had rejected its form. “Try to be one of us,” they had said, and I had not been able to. It was this that was haunting me though I would not admit it. I struggled against everything, it now seems clear, because I wanted to belong.

Then in sunlight the music floated over us and when it ended—the unachievable last parade as plebes—we turned and in a delirious moment, having forgotten everything, shook hands with our tormentors. They came along the ranks at ease seeking us out, and with self-loathing I found myself shaking hands with men I had sworn not to.

So the year ended. I have returned to it many times in dreams. The river is smooth and ice clings to its banks. The trees are bare. Through the open window from the far shore comes the sound of a train, the faint, distant clicking of wheels on the rail joints, the Albany or Montreal train with its lighted cars and white tablecloths, the blur of luxury from which we are ever barred.

At night the barracks, seen from the Plain, look like a city. All of us are within, unseen, studying determinants, general orders, law. I had walked the pavement of the interior quadrangles interminably, burning with anger against what I was required to be. In the darkness the uniform flags hung limply. In a few minutes it would be taps, then quickly the next day. Ten minutes to formation. What are we wearing? I ask. Where are we going? Bells begin to ring. People are vanishing. The room, the hallways are empty. Dressing, I run down the stairs.

That summer, after leave, we went into the field and to a camp by a lake, wooden barracks, firing ranges, and maneuver grounds of all kinds. Yearling summer. In the new and sunny freedom, weedy friendships grew. We fired machine guns and learned to roll cigarettes by hand. In off-hours I lay on my bed, reading. I knew lines of Powys’s Love and Death by heart and reserved them for a slim, witty girl who came up from New York on several weekends. She was the daughter of a famous newspaperman. We danced, swam, and went for walks in permitted areas, where the sensuous phrases fell to the ground, useless against her. I was disappointed. The words had been written by someone else but I had assumed them, they were my own. I was posing as part of a doomed generation, They shall not grow old, as we who are left grow old…. She did not take it seriously. “Kiss the back of your letters, will you?” I asked her. Such things were noticed by the mail orderly.

There is a final week of maneuvers before we return to the post, of digging when exhausted and then being told abruptly that we are moving to different positions; and deeper, they say, dig deeper. There is the new, energetic company commander with wens on his face who seems to like me and for whom, exhilarated, I would do anything. His affection for me was probably imagined, but mine for him was not. He was someone for whom I had waited impatiently, intelligent, patrician, and governed by a sense of duty—this became a significant word, something valuable, like a dense metal buried in the earth that could guide one’s actions. There were things that must be done; there were faces that would be turned toward yours and rely on you.

That year we studied Napoleon and obscure campaigns around Lake Garda. There were arrows of red and blue printed on the map but little in the way of thrilling detail, the distant ranks at Eylau, the fires, the snow, the wan-faced emperor wearing sable, the obscure horizon and arms reaching out. We studied movement and numbers. We studied leadership, in part from German texts, given to us not so much to know the enemy but because of their quality, with nothing in them of politics or race.

There was one with the title Der Kompaniechef, the company commander. This youthful but experienced figure was nothing less than a living example to each of his men. Alone, half-obscured by those he commanded, similar to them but without their faults, self-disciplined, modest, cheerful, he was at the same time both master and servant, each of admirable character. His real authority was not based on shoulder straps or rank but on a model life that granted the right to demand anything from others.

An officer, wrote Dumas, is like a father with greater responsibilities than an ordinary father. The food his men ate, he ate, and only when the last of them slept exhausted did he go to sleep himself. His privilege lay in being given these obligations and a harder duty than any of the rest.

The company commander was someone whom difficulties could not dishearten, privation could not crush. It was not his strength that was unbreakable but something deeper, his spirit. He must not only have his men obey, they must do it when they are absolutely worn out and quarreling among themselves, when they are at the end of their ropes and another senseless order comes down from above.

He could be severe but only when it was needed and then briefly. It had to be just, it had to wash things clean like a sudden, fierce storm. When he looked over his men he was conscious that 150 families had placed a son in his care. Sometimes, unannounced, he went among these sons in the evening to talk or just sit and drink a beer, not in the role of superior but of an older, sympathetic comrade. He went among them as kings once went unknown among their subjects, to hear their real thoughts and to know them. Among his most important traits were decency and compassion. He was not unfeeling, not made of wood. Especially in time of grief, as a death in a soldier’s family at home, he brought this news himself—no one else should be expected to—and granted leave, if possible, even before it was asked for, in his own words expressing sympathy. Ties like this would never be broken.

This was not the parade-ground captain, the mannequin promoted for a spotless record. It was not someone behind the lines, some careerist with ambitions. It was another breed, someone whose life was joined with that of his men, someone hardened and uncomplaining, upon whom the entire struggle somehow depended, someone almost fated to fall.

I knew this hypothetical figure. I had seen him as a schoolboy, latent among the sixth formers, and at times had caught a glimpse of him at West Point. Stroke by stroke, the description of him was like seeing a portrait emerging. I was almost afraid to recognize the face. In it was no self-importance; that had been thrown away, we are beyond that, stripped of it. When I read that among the desired traits of the leader was a sense of humor that marked a balanced and indomitable outlook, when I realized that every quality was one in which I instinctively believed, I felt an overwhelming happiness, like seeing a card you cannot believe you are lucky enough to have drawn, at this moment, in this game.

I did not dare to believe it but I imagined, I thought, I somehow dreamed the face was my own.

I began to change, not what I was truly but what I seemed to be. Dissatisfied, eager to become better, I shed as if they were old clothes the laziness and rebellion of the first year and began anew.

I was undergoing a conversion, from a self divided and consciously inferior, as William James described it, to one that was unified and, to use his word, right. I saw myself as the heir of many strangers, the faces of those who had gone before, my new roommate’s brother, for one, John Eckert, who had graduated two years earlier and was now a medium bomber pilot in England. I had a photograph of him and his wife that I kept in my desk, the pilot with his rakish hat, the young wife, the clarity of their features, the distinction. Perhaps it was in part because of this snapshot that I thought of becoming a pilot. At least it was one more branch thrown onto the pyre. When he was killed on a mission not long after, I felt a secret thrill and envy. His life, the scraps I knew of it, seemed worthy, complete. He had left something behind, a woman who could never forget him, I had her picture. Death seemed the purest act. Comfortably distant from it I had no fear.

There were images of the struggle in the air on every side, the worn fighter pilots back from missions far into Europe, rendezvous times still written in ink on the backs of their hands, gunners with shawls of bullets over their shoulders, grinning and risky, I saw them, I saw myself, in the rattle and thunder of takeoff, the world of warm cots, cigarettes, stand-downs, everything that had mattered falling away. Then the long hours of nervousness as the formation went deeper and deeper into enemy skies and suddenly, called out by jittery voices, high above, the first of them appear, floating harmlessly, then turning, falling, firing, plummeting past, untouchable in their speed. The guns are going everywhere; the sky is filled with smoke and dark explosions and then it happens, something great and crucial tearing from the ship, a vast flat of wing, and we begin to roll over, slowly at first and then faster, screaming to one another, going down.

That was death: to leave behind a photograph, a twenty-year-old wife, the story of how it happened. What more is there to wish than to be remembered? To go on living in the narrative of others? More than anything I felt the desire to be rid of the undistinguished past, to belong to nothing and to no one beyond the war. At the same time I longed for the opposite, country, family, God, perhaps not in that order. In death I would have them or be done with the need; I would be at last the other I yearned to be.

That person in the army, that wasn’t me, Cheever wrote after the war. In my case, it was. I did not know the army meant bad teeth, drab quarters, men with small minds, and colonels wearing sunglasses. Anyone from the life below can be a soldier. I imagined campaigns like Caesar’s, the sun going down in wooded country, encampments on hilltops, cool dawns. The army was that; it was like a beautifully dressed woman, I saw her smile at me and stood erect.

The army. They are playing the last songs at the hop, the sentimental favorites. I am dancing with a girl named Pat Potter, blond and elegant, whom I somehow knew. There are moments when one is part of the real beauty, the pageant. They are playing “Army Blue,” the matrimonial and farewell song. A hundred, two hundred couples are on the floor. The army. Familiar faces. This immense brotherhood in which they bend you slowly to their ways. This great family in which one is always advancing, even while asleep.

There was a special physical examination that winter that included the eyes, aligning two pegs in a sort of lighted shoe box by pulling strings, “Am I good enough for the Air Corps, sir?” and identifying colors by picking up various balls of yarn. In April 1944, those who had passed, hundreds of us, including my two roommates and me, left for flight training in the South and Southwest. Hardly believing our good fortune we went as if it were a holiday, by train. Left behind were classes, inspections, and many full-dress parades. Ahead was freedom and the joy of months away.

We were gone all spring and summer and returned much changed. We marched less perfectly, dressed with less care. West Point, its officers’ sashes and cock feathers fluttering from shakos, its stewardship, somehow passed over to those who had stayed.

In the fall of 1944, amid the battles on the Continent, came word of the death of Benny Mills. He was killed in action in Belgium, a company commander. Beneath a shroud his body had lain in the square of a small town; people had placed flowers around it and his men, one by one, saluted as they passed through and left him, like Sir John Moore at Corunna, alone with his glory. He had fallen and in that act been preserved, made untarnishable. He had not married. He had left no one.

His death was one of many and sped away quickly, like an oar swirl. I could never imitate him, I knew, or be like him. He was part of a great dynamic of which I, in a useless way, was also part, and classmates, women, his men, all had more reason to remember him than I, but it may have been for some of them as it was for me: He represented the flawless and was the first of that category to disappear.

We bought officers’ uniforms from military clothiers who came on weekends in the spring and set up tables and racks in the gymnasium. The pleasure of examining and choosing clothes and various pieces of decoration—should pilot’s wings be embroidered in handsome silver thread or merely be a metal version, was it worthwhile to order one or two handmade “green” shirts, was the hat to be Bancroft or Luxemburg—all this was savored. Luxemburg, thought to be the very finest, was in fact two tailor brothers surrounded by walls of signed photographs in their New York offices. The pair of them were to the army as Babel was to the Cossacks.

Like young priests or brides, immaculately dressed, filled with vision, pride, and barely any knowledge, we would go forth. The army would care for us. We had little idea of how careers were fashioned or generals made. Napoleon, I remembered, when he no longer knew personally all those recommended for promotion, would jot next to a strange name on the list three words: Is he lucky? And of course I would be.

At Stewart Field that final spring, nearly pilots, we had the last segment of training. This was near Newburgh, about forty minutes from West Point. We wore flying suits most of the day and lived in long, open-bay barracks. That photograph of oneself, unfading, that no one ever sees, in my case was taken in the morning by the doorway of what must be the dayroom and I am drinking a Coke from an icy, greenish bottle, a delicious prelude to all the breakfastless mornings of flying that were to come. During all the training there had been few fatalities. We were that good. At least I knew I was.

On a May evening after supper we took off, one by one, on a navigation flight. It was still daylight and the planes, as they departed, were thrilling in their solitude. On the maps the course was drawn, miles marked off in ticks of ten. The route lay to the west, over the wedged-up Allegheny ridges to Port Jervis and Scranton, then down to Reading, and the last long leg of the triangle back home. It was all mechanical with one exception: The winds aloft had been incorrectly forecast. Unknown to us, they were from a different direction and stronger. Alone and confident we headed west.

The air at altitude has a different smell, metallic and faintly tinged with gasoline or exhaust. The ground floats by with tidal slowness, roads desolate, the rivers unmoving. It is exactly like the map with certain insignificant differences that one ponders over but leaves unresolved. The sun has turned red and sunk lower. The airspeed reads 160. The fifteen or twenty airplanes, invisible to one another, are in a long, phantom string. Behind, the sky has become a deeper shade. We were flying not only in the idleness of spring but in a kind of idyll that was the end of the war. The color of the earth was muted and the towns seemed empty shadows. There was no one to see or talk to. The wind, unsuspected, was shifting us slowly, like sand.

Of what was I thinking? The inexactness of navigation, I suppose, New York nights, the lure of the city, various achievements that a year or two before I had only dreamed of. The first dim star appeared and then, somewhat to the left of where it should be, the drab scrawl of Scranton.

Flying, like most things of consequence, is method. Though I did not know it then, I was behaving offhandedly. There were light lines between cities in those days, like lights on an unseen highway but much further apart. By reading their flashed codes you could tell where you were, but I was not bothering with that. I turned south toward Reading. The sky was dark now. Far below, the earth was cooling, giving up the heat of the day. A mist had begun to form. In it, the light lines would fade away and also, almost shyly, the towns. I flew on.

It is a different world at night. The instruments become harder to read, details disappear from the map. After a while I tuned to the Reading frequency and managed to pick up its signal. I had no radio compass but there was a way of determining, by flying a certain sequence of headings, where you were. If the signal slowly increased in strength you were inbound toward the station. If not and you had to turn up the volume to continue hearing it, you were going away. It was primitive but it worked. When the time came I waited to see if I had passed or was still approaching Reading. The minutes went by. At first I couldn’t detect a change but then the signal seemed to grow weaker. I turned north and flew watching the clock. Something was wrong, something serious: The signal didn’t change. I was lost, not only literally but in relation to reality. Meanwhile the wind, unseen, fateful, was forcing me further north.

Among the stars, one was moving. It was the lights of another plane, perhaps from the squadron. In any case, wherever it was headed there would be a field. I pushed up the throttle. As I drew closer, I began to make out what it was, an airliner, a DC-3. It might be going to St. Louis or Chicago. I had already been flying for what seemed like hours and had begun, weakhearted, a repeated checking of fuel. The gauges were on the floor. I tried not to think of them but they were like a wound; I could not keep myself from glancing down.

Slowly the airliner and its lights became more distant. I turned northeast, the general direction of home. I had been scribbling illegibly on the page of memory which way I had gone and for how long. I now had no idea where I was. The occasional lights on the ground of unknown towns, lights blurred and yellowish, meant nothing. Allentown, which should have been somewhere, never appeared. There was a terrible temptation to abandon everything, to give up, as with a hopeless puzzle. I had the greatest difficulty not praying and finally I did, flying in the noisy darkness, desperate for the sight of a city or anything that would give me my position.

In the map case of the airplane was a booklet, What to Do If Lost, and suddenly remembering it, I got it out and with my flashlight began to read. There was a list of half a dozen steps to take in order. My eye skidded down it. The first ones I had already tried. Others, like tuning in any radio range and orienting yourself on it, I had given up on. I managed to get the signal from Stewart Field but didn’t take up the prescribed heading. I could tell from its faintness—it was indistinct in a thicket of other sounds—that I was far away, and I had lost faith in the procedure. The final advice seemed more practical. If you think you are to the west of Stewart, it said, head east until you come to the Hudson River and then fly north or south, you will eventually come to New York or Albany.

It was past eleven, the sky dense with stars, the earth a void. I had turned east. The dimly lit fuel gauges read twenty-five gallons or so in each wing. The idea slowly growing, of opening the canopy and struggling into the wind, over the side into blackness, parachuting down, was not as unthinkable as that of giving the airplane itself up to destruction. I would be washed out, I knew. The anguish was unbearable. I had been flying east for ten minutes but it seemed hours. Occasionally I made out the paltry lights of some small town or group of houses, but otherwise nothing. The cities had vanished, sunken to darkness. I looked down again. Twenty gallons.

Suddenly off to the left there was a glimmer that became—I was just able to make it out—a faint string of lights and then slowly, magically, two parallel lines. It was the bridge at Poughkeepsie! Dazed with relief I tried to pick out its dark lines and those of the river, turning to keep it in sight, going lower and lower. Then in the way that all things certain had changed that night, the bridge changed, too. At about a thousand feet above them, stricken, I saw I was looking at the streetlights of some town.

The gauges read fifteen gallons. One thing that should never be done—it had been repeated to us often—was to attempt a forced landing at night. But I had no choice. I began to circle, able in the mist to see clearly only what was just beneath. The town was at the edge of some hills; I banked away from them in the blackness. If I went too far from the brightly lit, abandoned main street, I lost my bearings. Dropping even lower I saw dark roofs everywhere and amid them, unexpectedly, a blank area like a lake or small park. I had passed it quickly, turned, and lost it. Finally, lower still, I saw it again. It was not big but there was nothing else. I ducked my head for a moment to look down—the number beneath each index line was wavering slightly; ten gallons, perhaps twelve.

The rule for any strange field was to first fly across at minimum altitude to examine the surface. I was not even sure it was a field; it might be water or a patch of woods. If a park, it might have buildings or fences. I turned onto a downwind leg or what I judged to be one, then a base leg, letting down over swiftly enlarging roofs. I had the canopy open to cut reflection, the ghostly duplication of instruments and warning lights. I stared ahead through the wind and noise. I was at a hundred feet or so, flaps down, still descending. In front, coming fast, was my field. On a panel near my knee were the landing-light switches with balled tips to make them identifiable by feel. I reached for them blindly. The instant they came on I knew I’d made a mistake. They blazed like searchlights in the mist; I could see more without them but the ground was twenty feet beneath me, I was at minimum speed and dared not bend to turn them off. Something went by on the left. Trees, in the middle of the park. I had barely missed them. No landing here. A moment later, at the far end, more trees. They were higher than I was, and without speed to climb I banked to get through them. I heard foliage slap the wings as just ahead, shielded, a second rank of trees appeared. There was no time to do anything. Something great struck a wing. It tore away. The plane careened up. It stood poised for an endless moment, one landing light flooding a house into which an instant later it crashed.

Nothing has vanished, not even the stunned first seconds of silence, the torn leaves drifting down. Reflexively, as a slain man might bewilderedly shut a door, I reached to turn off the ignition. I was badly injured, though in what way I did not know. There was no pain. My legs, I realized. I tried to move them. Nothing seemed wrong. My front teeth were loose; I could feel them move as I breathed. In absolute quiet I sat for a few moments at a loss, then unbuckled the harness and stepped over the cockpit onto what had been the front porch. The nose of the plane was in the wreckage of a room. The severed wing lay back in the street.

The house, as it turned out, belonged to a family that was welcoming home a son who had been a prisoner of war in Germany. They were having a party and had taken the startling noise of the plane as it passed low over town many times to be some sort of military salute and though it was nearly midnight had all gone into the street to have a look. I had come in like a meteorite over their heads. The town was Great Barrington. I had to be shown where it was on a map, in Massachusetts, miles to the north and east.

That night I slept in the mayor’s house, in a feather bed. I say slept but in fact I hung endlessly in the tilted darkness, the landing light pouring down at the large frame house. The wing came off countless times. I turned over in bed and began again.

They came for me the next day in a wrecking truck and I rode back with the remains of the plane. In the barracks, which were empty when I arrived, my bed was littered with messages, all mock congratulations. I found myself, unexpectedly, a popular figure. It was as if I had somehow defied the authorities. On the blackboard in the briefing room was a drawing of a house with the tail of an airplane sticking from the roof and written beneath, GEISLER’S STUDENT. I survived the obligatory check rides and the proceedings of the accident board, which were unexpectedly brief. Gradually transformed into a comedy, the story was told by me many times as I felt, for one shameless instant, it would be that night when the boughs of the first trees hit the wings before I saw the second. There was a bent, enameled Pratt and Whitney emblem from the engine that I kept for a long time until it was lost somewhere, and years later a single unsigned postcard reached me, addressed care of The Adjutant General. It was from Great Barrington. We are still praying for you here, it said.

Confident and indestructible now, I put a dummy of dirty clothes in my bed and one night after taps met Horner near the barracks door. We were going off limits, over the fence, the punishment for which was severe. Graduation was only days away; if we were caught there would be no time for confinement to quarters or walking the Area; the sentence would be more lasting: late graduation and loss of class standing. The risk, though, was not great. “Anita is coming up,” he told me. “She’s bringing a girlfriend.” They would be waiting in a convertible at the bottom of a hill.

Anita was new. I admired her. She was the kind of girl I would never have, who bored me, in fact, and was made intriguing only by the mischievous behavior of Horner. In some ways I was in that position myself, his Pinocchio, willing and enthralled.

Anita was the daughter of a carpet manufacturer. She wore silk stockings and print dresses. She had red fingernails and was tall. Her efforts to discipline Horner were ineffective and charming. “Well, you know Jack…” she would explain helplessly. I did know him and liked him, I think, at least as much as she did and probably for longer.

Staying close to the buildings we made it in the darkness to the open space near the fence and climbed over quickly. The road was not too long a walk away. We came over a slight crest and halfway down the hill, delirious in our goatlike freedom, saw the faint lights of the dashboard. One of the doors was open, the radio was softly playing. Two faces turned to us. Anita was smiling. “Where the hell have you been?” she said, and we drove off toward Newburgh to find a liquor store. Jack was in front with her; their laughter streamed back like smoke.

The Anitas. I had more or less forgotten them. Ages later, decades literally, in the deepest part of the night the telephone rings in the darkness and I reach for it. It’s 2:00 in the morning, the house is asleep. There is a cackle that I recognize immediately. “Who is this?” I say. To someone else, aside, gleefully he says, “He wants to know who it is.” Then to me, “Did I wake you up?”

“What could possibly give you that idea?”

Another cackle. “Jim, this is Jack Homer,” he says in a businessman’s voice. He was divorced and traveling around. Doing what? I ask. “Inspecting post offices,” he says. Bobbing around his voice are others, careless, soft as feathers. One of them comes on the phone. “Where are you?” I ask. My wife is sleeping beside me. A low voice replies, “In a motel. About three blocks from you.” In the background I can hear him telling them I am a writer, he has known me since we were cadets. He tries to take the phone again. I can hear them struggling, the laughter of the women and his own, high and almost as feminine, infectious.

That May night, however, we parked near an orchard and went up beneath the trees. We got back to the barracks very late. A day or two afterward I came up to him while he was shaving before breakfast. “Have you noticed anything strange?” I asked. “Yes. What is it? Have you got it, too?” It was a rash. It turned out to be poison ivy covering our arms and legs, a first mock rendering to Venus.

We went without neckties, excused from formation. Skin blistered and unable to wear a full dress coat, I stood at the window of my room and heard the band playing in the distance and the long pauses that were part of the ceremony of the last parade. There came the sound of the music played just once a year when the graduating class, some of them openly weeping, removed their hats as the first of the companies, in salute, came abreast, officers’ sabers coming up, glinting, then whipping downward.

Far off, the long years were passing in review, the seasons and settings, the cold walls and sally ports, the endless routine. Through high windows the sun fell on the choir as it came with majestic slowness, singing, up the aisle. The uniforms, the rifles, the books. The winter mornings, dark outside, smoking and listening to the radio as we cleaned the room. The gym, dank and forbidding. The class sections forming in haste along the road.

The Area was filled with footlockers and boxes. Everyone would be leaving, scattered, dismissed for the last time, to the chapel for weddings, to restaurants with their families, to the coast, the Midwest, to the smallest of towns. We were comparing orders, destinations. I felt both happiness and the pain of farewell. We were entering the army, which was like a huge, deep lake, slower and deeper than one dreamed. At the bottom it was fed by springs, fresh and everlastingly pure. On the surface, near the spillway, the water was older and less clear, but this water was soon to leave. We were the new and untainted.

On my finger I had a gold ring with the year of my class on it, a ring that would be recognizable to everyone I would meet. I wore it always; I flew with it on my finger; it lay in my shoe while I slept. It signified everything, and I had given everything to have it. I also had a silver identification bracelet all flyers wore, with a welt of metal that rang when it touched the table or bar. I was arrogant, perhaps, different from the boy who had come here and different even from the others, not quite knowing how, or the danger.

As we packed to leave, a pair of my roommate’s shoe trees got mixed up with mine. I did not notice it until after we had gone. In a hand distinctly his, ECKERT, R.P. in ink was neatly printed on the wooden toe block. He was killed later in a crash, like his brother. His life disappeared but not his name, which I saw over the years as I dressed and then saw him, cool blue eyes as if faded, pale skin, a way of smoking that was oddly abrupt, a way of walking with his feet turned out. I also kept a shako, some pants, and a gray shirt, but slowly, like paint flaking away, they were left behind or lost, though in memory very clear.

One thing I saw again, long afterward. I was driving on a lonely road in the West about twenty miles out of Cheyenne. It was winter and the snow had drifted. I tried to push through but in the end got stuck. It was late in the afternoon. The wind was blowing. There was not a house to be seen in any direction, only fences and flat, buried fields.

I got out and started back along the road. It was very cold; my tire tracks were already being erased. Gloved hands over my ears, I was alternately walking and running, thinking of the outcome of Jack London stories. After a mile or two I heard dogs barking. Off to the right, half-hidden in the snow, was a plain, unpainted house and some sheds. I struggled through the drifts, the dogs retreating before me, barking and growling, the fur erect on their necks.

A tall young woman with an open face and a chipped tooth came to the door. I could hear a child crying. I told her what had happened and asked if I could borrow a shovel. “Come in,” she said.

The room was drab. Some chairs and a table, bare walls. She was calling into the kitchen for her husband. On top of an old file cabinet a black-and-white television was turned on. Suddenly I saw something familiar, out of the deepest past—covering the couch was a gray blanket, the dense gray of boyhood uniforms, with a black-and-gold border. I recognized it; it was a West Point blanket. Her husband was pulling on his shirt. How fitting, I thought, one ex-regular bumping into another in the tundra, years after, winter at its coldest, life at its ebb.

In a littered truck we drove back to the car and worked for an hour, hands gone numb, feet as well. Heroic labor, the kind that binds you to someone. We spoke little, only about shoveling and what to do. He was anonymous but in his face I saw patience, strength, and that ethic of those schooled to difficult things. Shoulder to shoulder we tried to move the car. He was that vanished man, the company commander, the untiring god of those years when nothing was higher; privations mean little to him, difficulties cannot break his spirit….

Together we rescued the car and back at the house I held out some money. I wanted to give him something for his trouble, I said. He looked at it. “That’s too much.”

“Not for me,” I said. Then I began, “Your blanket…”

“What blanket?”

“The one on the couch; I recognize it. Where’d you get it?” I said idly. He turned and looked at it, then at me as if deciding. He was tall, like his wife, and his movements were unhurried. “Where’d we get it?” he asked her. The ladies who come up in June … I thought. They’d been married in the chapel.

“That? I forget. At the thrift shop,” she said.

For a moment I thought they were acting, unwilling to reveal themselves, but no. He was a tattoo artist, it turned out. He worked in Cheyenne.